Hair Loss Research Focuses on Insulin

Some researchers believe Insulin resistance may be a focus for hair loss therapy in the future.

Insulin resistance and its role in diabetes has been known for decades and much research has led to advancements in Type II diabetic therapy. There are many known possible factors of developing diabetes. It has increasingly been found that that hair loss in some people may be due to insulin resistance and the topic is being studied by many leading hair loss research centers especially for cases of scarring alopecia.

Insulin resistance and its role in diabetes has been known for decades and much research has led to advancements in Type II diabetic therapy. There are many known possible factors of developing diabetes. It has increasingly been found that that hair loss in some people may be due to insulin resistance and the topic is being studied by many leading hair loss research centers especially for cases of scarring alopecia.

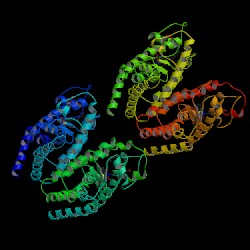

Recent research by Pratima Karnik, Ph.D., and investigators at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland and the University of California, San Francisco, found that the initiating event in the pathogenesis of scarring alopecia may be loss of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma function aka ppar-y. Their finding paves the way for clinical trials testing the hypothesis that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (ppar)-gamma upregulation may offer a novel means of treating scarring alopecia. The ppar-gamma agonists, thiazolidinediones and glitazones, are prescribed for glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes.

“This work about ppar-gamma is just so exciting. In just the next year or two, it could [make a difference] in the way we treat patients with cicatricial alopecia,” said Dr. Kenneth Washenik at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“This is a really, really important milestone paper,” said Dr. Washenik, a dermatologist at New York University and medical director at Bosley Medical, the nation’s largest hair restoration group.

The ground-breaking report included several related studies (J. Invest. Dermatol. 2008;129:1066-70). In one, the investigators performed gene microarray analysis using scalp biopsy specimens from patients with lichen planopilaris (LPP)–an inflammatory scarring hair disorder–and from normal controls. LPP patients had reduced expression of genes required for lipid metabolism and production of peroxisomes.

Immunohistochemical studies in lesional and uninvolved skin of LPP patients showed progressive loss of ppargamma activity and local accumulation of unprocessed lipids.

These lipids appeared to be proinflammatory. In areas of lesional skin they were accompanied by production of proinflammatory cytokines and infiltration of inflammatory cells, followed by the hallmark of LPP: the destruction of sebaceous glands and hair follicles, with resultant scarring.

The investigators also showed that ppar-gamma agonists induced peroxisomal and lipid metabolic gene expression in keratinocytes.

The clincher in making a case for loss of ppar-gamma function being the key initiating event in the pathogenesis of LPP–and by inference in the other cicatricial alopecia as well involved the investigators’ work with transgenic mice. The team created a knockout mouse model lacking ppar-gamma in follicular stem cells. These mice gradually developed a progressive scarring alopecia beginning at about age 4 weeks, with complete scarring alopecia by 4 months.

The mouse’s scarring alopecia looked histologically just like LPP: dystrophic hair follicles, follicular plugging, perifollicular fibrosis, and, most importantly, dystrophic sebaceous glands with perifollicular and interstitial inflammation.

Dr. Washenik noted that these new LPP studies are merely the latest in a series of reports suggesting a variety of potential dermatologic applications for glitazones.

Click here for hair loss product Zenagen